Medical transportation companies have been on federal and state regulatory radar for decades, for program integrity concerns such as fraudulent billing practices and patient safety concerns. Currently there are 812 names of individuals and entities related to transportation services on the OIG Exclusion List.

States are required to provide both emergency and non-emergency medical transport (NEMT) benefits to Medicaid beneficiaries but have considerable discretion in how to deliver the benefits. A wide range of methods are available for NEMT, including management of the benefit internally through the state departments of transportation, direct contracting with transportation providers paid on a fee-for-service basis, transportation brokers paid on a capitated basis, contracted managed care organizations (MCOs), and public transportation vouchers. As noted in Health Affairs, due to lags and gaps in national Medicaid data, it is challenging to compile a contemporary snapshot of NEMT usage, although transportation researchers at Texas A&M estimated $2.9 billion was expended on NEMT to provide 103.6 million NEMT trips in fiscal year 2013, and it has only increased since then as Medicaid plans have expanded eligibility.

For many years, the OIG and CMS have issued guidance documents to assist transportation suppliers to understand and meet regulatory requirements:

- In 2003, the Office of the Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services (OIG) issued guidance for ambulance suppliers with the stated purpose to engage the private health care community in preventing the submission of erroneous claims and in combating fraudulent and abusive conduct. This issuance included information about the ramifications of hiring or retaining excluded individuals or entities.

- In 2009, CMS issued guidance to state Medicaid agencies about the effect of exclusion on providers who are part of the state’s Medicaid program and gave a specific example related to transportation services which are not reimbursable: “Services performed by excluded ambulance drivers, dispatchers and other employees involved in providing transportation reimbursed by a Medicaid program, to hospital patients or nursing home residents”.

- In 2013, the OIG published definitive guidance, “The Effect of Exclusion from Participation in Federal Health Care Programs” which specifically stated, “Excluded individuals are prohibited from providing transportation services that are paid for by a Federal health care program, such as those provided by ambulance drivers or ambulance company dispatchers.”

- In 2016, CMS issued a booklet for providers to explain Non-Emergency Medical Transportation which explained the Medicaid benefit and also addressed fraud issues.

- Quite recently, on July 12, 2021, CMS issued a memo about Medicaid coverage of non-emergency medical transportation which was part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 (Public Law 116-260). As part of the requirements set forth therein, minimum requirements for state programs includes a provision that each transportation provider and individual driver must not be excluded from participation in any federal health care program and is not listed on the exclusion list of the OIG which is also referred to as the List of Excluded Individuals/Entities (LEIE).

Notwithstanding clear guidance over almost 2 decades, CMS and the OIG have continued to uncover instances of transportation companies that have not met the letter of the law when it came to billing, documentation and safety practices. In audit after audit after audit, the OIG has found state Medicaid transportation contractors deficient as to the data captured about their transport services as well as meeting state and federal requirements.

Cutting regulatory and legal corners in the transportation industry has been hard to detect because of its historic patchwork structure across the nation and often lax state oversight. As noted above, there are many models that a state can select and they have broad discretion in their choice. However, even states that have developed sound infrastructure to provide transportation needs through well-established private companies can experience significant fraud. The result has been that millions have been paid out to both large and small contractors on the basis of fraudulent claims. Below are but two examples of recent large settlements with the DOJ for false claims:

- In January of 2017, Medstar Ambulance Inc., including four subsidiary companies and its two owners, agreed to pay $12.7 million to resolve allegations that the ambulance company knowingly submitted false claims to Medicare. The settlement with the Department of Justice resolved allegations that from 2011 through 2014, Medstar routinely billed for services that did not qualify for reimbursement because the transports were not medically reasonable and necessary, billed for higher levels of services than were required by patients’ conditions, and billed for higher levels of services than were actually provided. As part of the settlement Medstar also agreed to a corporate integrity agreement with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

- In March of 2018, Medical Transport LLC, a Virginia Beach-based provider of ambulance services, agreed to pay $9 million to resolve allegations that it violated the False Claims Act by submitting false claims for ambulance transports. The government alleged that Medical Transport submitted false or fraudulent claims to Medicare, Medicaid, and TRICARE for ambulance transports that were not medically necessary, that did not qualify as Specialty Care Transports, and that were billed improperly to the federal health care programs when they should have been billed to other payers. As part of the settlement, Medical Transport entered into a five-year Corporate Integrity Agreement (CIA) with the HHS-OIG.

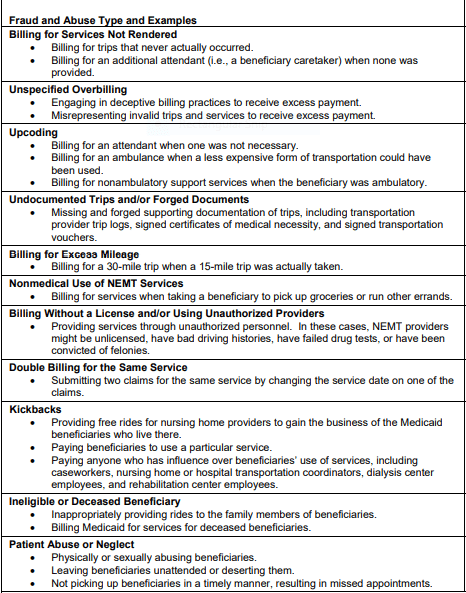

So, what are the most common types of schemes that transportation companies engage in to defraud CMS and state Medicaid programs? Below is a list of billing ploys used:

- Billing for transports that never occurred;

- Upcoding – billing for an attendant when one was not necessary or billing for an ambulance when a less expensive mode of transportation would have sufficed;

- Billing for excess mileage – for example, billing for 30 miles when the distance was 15 miles;

- Forging documentation of trips, including trip logs, signed certifications of medical necessity and signed transportation vouchers;

- Double-billing for the same service by changing the data of service on a second identical claim;

- Billing for non-medical transportation such as trips to the market;

- Providing services through unauthorized personnel. This can include unlicensed drivers, those with bad driving histories, those that have failed drug tests or which have been convicted of felonies;

- Billing for transports that occurred after a Medicaid recipient was deceased;

CONCLUSION

As a 2017 article in Health Affairs summarized bluntly:

“Program integrity lapses have damaged NEMTs’ reputation.”

However, there have been changes related to medical transportation contracting which have reduced the incidence of fraudulent billing and shady operations that put Medicaid recipients at risk and landed many of these vendors on the Medicaid Exclusion List. States have increasingly contracted with transportation brokers under a capitated payment arrangements so that while obtaining encounter data remains a challenge, the risk of billing irregularities has decreased. Also, adding transportation services to the list of benefits for which contracted Medicaid managed care organizations are responsible has shifted some of the burden of management and oversight off the states. The emergence of transportation network companies, such as Uber and Lyft, to provide non-emergency transportation has increased ride options in some areas but comes with its own complexities since those drivers are held to the same standards as any other contracted transport.

Federal agencies are committed to exposing those who would scam federal health care program – the number of excluded individuals and entities on the OIG Exclusion List reflect this. Also, the number of both DOJ prosecutions and settlements with transportation companies demonstrate the vigilance of state and federal agencies to identity and prosecute bad actors. However, the continual presence of enforcement actions demonstrates the ongoing need for strong program management and risk management strategies to protect the federal programs and the beneficiaries that they serve.